» An introductory teaser …

» on the importance of young internet users …

» for the development of democracy

just a medium…

…of expression!

The emergence of new communication systems is the result of complex interactions among technological, cultural, social, political and economic forces. This puts aside the belief that technologies have themselves an intrinsic power to shape society. Technology — in this case: communication tools — are just part of society and culture, a medium of expression. Therefore social changes cannot be directly identified in technology itself, but rather in its uses.

In the 90s, many studies focused on pathological users of the internet, stating that it creates an “unreal†world and that its users suffer from a lack of social capacities (see, for example, Chandler).

However, this discourse doesn’t seem to make sense today. Obviously there are always uses and abuses of technology, but we have different examples of the political use of the world wide web. Political, in this context, means all activities related to the public life.

In dictatorial regimes such as Belarus, to give but one example, the role that the internet plays for the opposition is well known. Similarly, anti-globalisation movements are often closely linked with new communication technologies.

Why? There are three main reasons: anonymity, geographical scope, and costs.

scope, and

costs.

Anonymity is an increasingly beneficial reality — at times when communication is observed and registered not only in political dictatorships. But it can also be of value for young people growing up in a more traditional context, where questioning about certain themes might be taboo. Available online information provides options and shows possibilities — an informational power of internet nobody could argue. And the very fact that the internet is an information medium makes it political — in the sense that it has and produces influence on social spheres and in public life.

The geographical scope of the internet is well-known, but it is worthwhile to remember that the internet is not global: it does not (yet) reach the entire world population. Economic and geographic disparities where shown by Pipa Norris in «The Digital Divide».

And the gap is not only between the Americas and Africa, or between Europe and Asia! That also, but the geographical divide also exists between Melnik and Sofia in Bulgaria, or between Salvaterra de Magos and Lisbon in Portugal. Inside the same country geographical divides are identifiable along distinctions between urban and rural or central and peripheral, often determined by economical differences or technological limitations.

And yet, part of today’s world population has access to the Internet; indeed, most people in developed countries have to use Internet in their daily life — be it at work, at home, or both.

The costs for providing and ensuring access to the internet are relatively low in comparison to other media. Think about the costs related to printing, add the environmental externalities and hold that against the investments related to internet access. Think about TV production costs and compare it with the maintenance of a weblog. And while costs can be a political question and pose the question if and how the state should interfere, the world wide web is definitely cheaper than many other media.

Partly due to the relatively low costs, the internet facilitates the diversification of communication channels. This is politically important because it expands the range of voices that can express themselves. Furthermore, mass media could be (and sometimes are) interpreted as a construct of capitalism, based on consumption as a tool for manufacturing consent. Because of its decentralized nature, low cost and easiness of creating (new, alternative) content, the internet — and new media in general — offer the attractiveness of many-to-many communication patterns. This can also be a metaphor of a changing society, more open, more diverse… and eventually more diffuse?

internet

foster

participation?!

This line of thought raises another question: can the internet foster participation? The internet’s comparatively low entry barriers ensure greater access to innovative (or even, at times, revolutionary) ideas. Simultaneously it allows for the circulation of a greater number of messages.

But… how many can actually be heard, read or listened to!?

If everyone is speaking at once, who is listening?

The social potential of new technologies is determined by their own nature: they are intrinsically different from other media. Unlike mass media, new technologies are not based on a communication system centred on the producer. The economies of scale — that are so characteristic of mass media production and consumption — are not to be found in the same manner in new media technologies.

Traditional mass media may currently have an enormous social power that is based on their ability to deliver huge quantities of information to large numbers of people in short time-spans. However, information reception is often passive and rarely involves thought and learning — one of the main criticisms put forward by the Frankfurt School, arguing that mass media favoured the passive reception of information and entertainment over thoughtful engagement and re-action.

New communication technologies can be used synchronously or asynchronously, which offers the chance to debate, but also the needed time to think and deliberate — with obvious advantages to negotiation and political discussion. However, one has to be critical towards the offer of content — as Benjamin Barber argues, variety is not the same as segmentation and abundance does not mean pluralism of content. The main risk of segmentation is that, in an extreme case, it destroys the common ground on which we base our shared working, living and co-operating.

Therefore, it is essential to find ways of bringing together people with different interests. It is vital for the social existence of democracy in complex societies where common life shall be ruled by common decisions. And in this sense, it is finally also essential to think about youth participation and the internet.

We all know the argument that young people are the future of society — and they also are, already now, the main users of new technologies; many times even their most creative users. Future generations will use technology in ways we cannot even think about today! And their imaginative uses might turn out quite different from those that we expect: just think about the importance of image over text today…

These — often co-existing and co-evolving — changes of paradigms are important for democracy.

And yet, the effect of change is barely calculable, and it may well become a part of youth work to help identify resulting opportunities and chances — for which youth workers need to observe and comprehend the uses of technology by young people.

These observations should never be understood or misused as a value-based evaluation returning positive or negative results. Much rather, it should come with a humble and constructive approach that is based on sharing and partaking and focuses on and highlights potential.

If youth work adopts an activist participatory approach in observing the influence of electronically mediated social and participatory networking of young people, we might eventually begin to understand how the social use of new technologies can affect personalities, human relations and the political system.

Comments

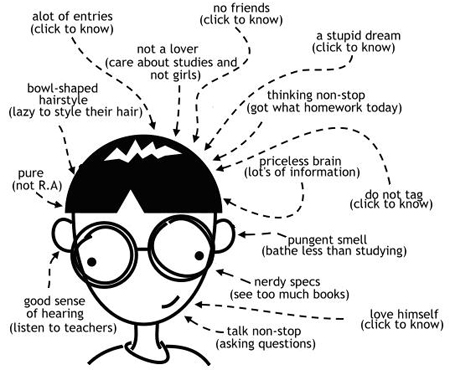

One response to “Why do we need the nerds?”

The *first* sentence (followed by many others) that makes me think is this one:

I wonder whether this is true—looking at learning and how it is changing through technology, for example. How the availability of technology puts educational institutions in a position where they are no longer the only providers of knowledge, and how this new situation—the possibility to engage in informal learning online, the chance to engage in informal, changing networks of informal learners on the web—forces education providers to react…

It may be that the technology was not invented with this particular purpose in mind—possibly not even with this particular consequence being considered at all, not even as a side-effect—but nonetheless: technology does change education, and society.

Yet I wonder–how intrinsic is this capacity for change? Is it inherent to technology, no matter what the context is? Or is it indeed an extrinsic capacity for change, utterly dependent on the fact that knowledge-based, knowledge-limited education is rusty and antiquated?

Ha, so many things to think about!

…